A menu can be a powerful storyteller, especially in Iceland, where its culinary narrative unfolds with native horses and sheep grazing fields blanketed with herbs and berries. As I drive Iceland’s Ring Road to the country’s western end, I snap photos of these pony-sized horses frolicking in mountainside pastures blanketed with herbs and berries. This is a prelude to my moment of culinary bravery.

A few days later, I’m in the kitchen with Hotel Husafell Head Chef Ingolfur Piffl as he hands me an artfully plated Icelandic horse tataki glazed with nitsume. I survey the slivers of marbled meat drizzled in sauce and garnished, trying not to think of those bucolic images I saw en route to the western Iceland property.

By the last day of my five-day trip, I had cultivated a level of culinary trust with Chef “Ingo,” having dined nightly on his dishes while exploring western Iceland by day.

Venturing outside of my culinary comfort zone is central to my experience of a destination.

Horse Tataki: A Unique Icelandic Dish

Chef Ingo’s horse tataki dish combines Asian and French cooking techniques, with horsemeat as the culinary canvas. His horse tataki sits on a foundation of barley sourdough brioche grilled in brown butter, a layer of stewed onions, and pickled Icelandic moss, topped with a spicy sauce made from Icelandic dried seafood and horse bacon and garnished with some Icelandic wasabi leaves. Chef Ingo forages many of the dish’s ingredients from the hotel’s property.

“Horsemeat is known as the Icelandic beef,” he says. “It’s a wild product cultivated in the country with no hormones injected into it, and it has a unique taste.”

According to written records, the first Norse settlers brought horses to Iceland in the 9th century. Iceland’s horse population maintains a pure bloodline dating back to the Vikings. Modern-day laws forbid the importation of horses and the reentry of native horses that leave the country.

Chef Ingolfur Piffl: Culinary Brilliance at Hotel Husafell

Chef Ingo, a highly educated and trained chef, has over 20 years of experience cooking in various establishments worldwide, including 5-star hotels and Michelin-star restaurants.

Iceland offers some of the world’s purest ingredients, he says, from its glacial water, native livestock, fresh seafood, chemical-free herbs, and produce. In recent years, Icelandic cuisine has gained culinary respect for capitalizing on its homegrown ingredients and ingenuity.

“I see food as a great connector that brings people together in a stronger way than craftsmanship. I present people with a meal that connects this all together,” Ingo says.

Iceland’s location along the North Atlantic Sea provides a bounty of seafood that serves as an economic mainstay.

“Icelandic fishing has been a lifeline for this island nation and functions as a main food source and an export product,” Chef Ingo explains. “Fish exports have been recorded as far back as the 12th century. Fishing will always be an integral part of Icelandic culture and history.”

Traditional Icelandic Breads

A taste for Iceland’s heritage manifests in several mainstay dishes unique to Icelanders. Icelandic rye bread, which goes by several names, including Lavabread, Volcano Bread, Thunder Bread, Pot bread, and/or Geyserbread. They are the most popular breads in Iceland.

“Originally, Icelandic rye bread was made from sourdough, which is naturally fermented,” the chef explains. “Many households didn’t have ovens until the start of the 20th century. Icelanders cooked the bread dough in pots over stove embers, relying on low heat and a long baking time.” With the invention of the electric oven and the availability of rising agents, Icelanders now use sugar or syrup to shorten the baking time.,” Chef Ingo explains.

Hearty Icelandic Comfort Food: Kjötsúpa

Many Icelandic dishes evolved from a need to stay warm and eat hearty, which led to the creation of a cultural resourcefulness that created dishes such as Icelandic meat soup called Kjötsúpa. It’s a menu staple in many households, with recipes that have endured for generations. Kjötsúpa comprises lamb meat, root vegetables like such as potatoes, turnips, and rutabagas, as well as various herbs and spices.

“The hearty vegetables added calories and vital nutrients and were reliable to keep throughout the winter. The lamb was a dense, tasty protein readily available in all parts of the country,” Ingo says.

Unique Icelandic Dishes: Fermented Hákarl

He says Icelandic seafood dishes have an underlying sweetness from a diverse and natural diet of smaller fish, crustaceans, and plankton. “This varied diet influences the flavor profile of the fish, introducing subtle notes that reflect the marine ecosystem. These flavors are unique and contribute to the complexity and depth of the fish’s taste,” Ingo says.

Fermented shark, known as Hákarl or kæstur hákarl, is a palatable and safe way to eat sharks. “The native dish consists of a Greenland or basking shark cured with fermentation and hung to dry in an open-air shed. Fresh shark meat is considered poisonous, and only after fermentation and drying in winter can it be eaten,” Ingo explains.

Sustainable Cooking Practices in Iceland

Chef Ingo cooks sustainably, sourcing many ingredients from Icelandic greenhouse farmers to reduce the CO2 footprint. He also started a small greenhouse project on the hotel property where he works that grows edible flowers and mushrooms. The entire kitchen staff works to reduce single-use products in the kitchen, like baking paper, plastic wrap, and single-use plastic boxes.

Lamb: A Culinary Staple in Iceland

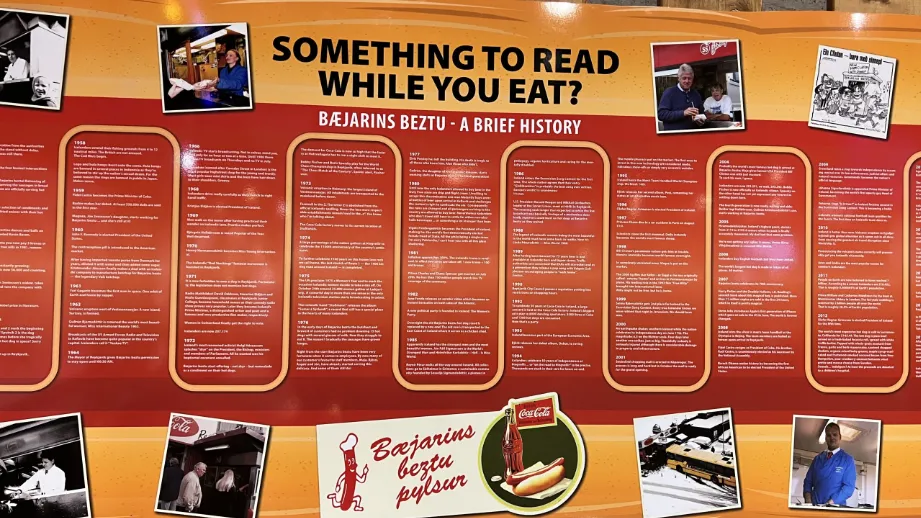

Lamb remains a popular meat in Icelandic cuisine, from fine dining to fast food. Reykejavik’s famous lamb hotdogs are served at Bæjarins Beztu (Translated to The Bezt in Town!).

Iceland’s oldest hot dog stand has been operating continuously in the same spot since 1937, regardless of the weather. The hot dog maker explains that these Icelandic hotdogs are made from three kinds of meat: 80 percent lamb, 10 percent pork, and 10 percent beef mixed together.

The local way to order is to ask for the One with Everything. It comes with mustard, Icelandic sauce, fried onions, raw onions, and that special apple ketchup.

Brennivin: Iceland’s National Drink

Iceland’s national drink is Brennivin, also known as The Black Death. It is made from caraway and cumin spices. Icelanders typically consume Brenninvin chilled as a shot, although the flavored spirit is also served in cocktails. Brenninvin packs a powerful punch to the tastebuds, with an aftertaste that, for me, tastes like part licorice and cough medicine.

Experience the Essence of Icelandic Cuisine

As a traveler, cuisine offers a portal to the soul of a culture—the traditions and values expressed in meals. Icelandic cuisine conveys an origin story of resilience and ingenuity, at times daring you to step outside your culinary comfort zone for a memorable and flavorful sensory experience.

For more travel insight, watch The Design Tourist Explores Iceland’s South Coast

To learn more about Icelandic food and other geological wonders, watch The Design Tourist Explores Iceland: Pass Less Traveled

More Helpful Posts When Exploring Iceland

Discover Iceland’s South Coast Hidden Wonders

Unique Iceland Bucket List: 8 Off-the-Beaten-Path Locations

Best Time for Iceland: Top Places by Season