As a child growing up in South Louisiana, plantation home tours comprised family outings and school field trips. The tours were romanticized narratives of the Antebellum South, with visions of beautiful southern belles in hoop-skirted dresses sipping mint juleps among the moss-draped oaks. This storybook narrative of Louisiana’s tumultuous agricultural past was the myth that sold admission tickets to tour opulent halls, luxurious furnishings, and the objects of wealthy planters in the 1800s.

Today, a reckoning with Louisiana’s slavery legacy is taking place as plantations reframe and retell their histories. Shadows on the Teche leads a growing movement across the Antebellum South to reconcile the whitewashing of history. The National Trust for Historic Preservation initiated the new narrative and helped fund the exhibit A Picture, Unbroken, which is on view across the street at the visitor’s center.

Historical Background

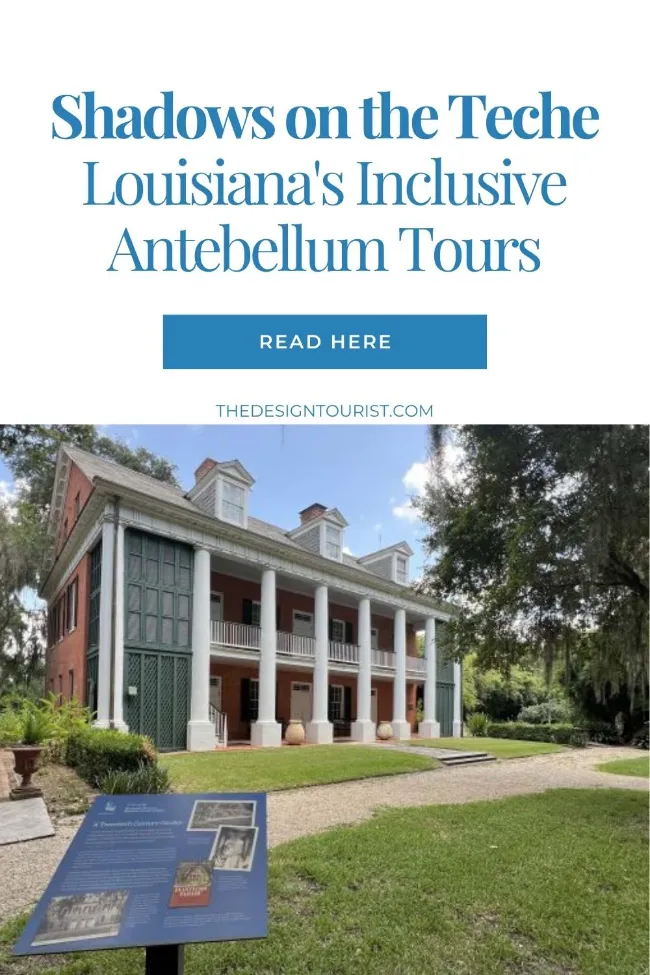

Shadows on the Teche was built in 1834 by David and Mary Weeks, who moved from England to establish the sugar plantation. The plantation home in New Iberia stands on the banks of Bayou Teche as a landmark of contradictions, chronicling a time in Louisiana’s history when agricultural prosperity was fueled by enslaved labor. Its graceful façade, framed by oak trees, conveys the glamorous curb appeal befitting wealthy planters in the 1800s Louisiana South.

“The Weeks family had nine plantations across the state and enslaved 1112 people. Slave labor built their wealth and the sugar industry in Louisiana. We need to recognize that fact and tell the entire story,” says Adam Foreman, Senior Manager of Interpretation and Education at Shadows on the Teche.

For four generations, the Weeks family lived at the home and ran a prosperous sugarcane plantation nearby on Weeks Island. The plantation’s original owners, David and Mary Weeks, were wealthy planters who enslaved hundreds of men, women, and children who lived and labored at the home and nearby sugar plantation, Weeks Island.

Transition to Museum

The last surviving owner, William Weeks Hall, a painter and eccentric socialite, died in 1958 and donated the home to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. In 1961, The National Trust opened the house as a plantation museum. “Originally, the narrative focused on the Weeks family experience and did not talk about the lives and experiences of the enslaved people who lived and worked on the plantation,” says John Warner Smith, Executive Director of Shadows on the Teche.

New Narrative and Exhibit

In May of 2023, Shadows on the Teche reopened its visitor’s center with a new, inclusive narrative in an accurate rendering of Louisiana’s Antebellum past. The exhibit moves through time, starting with Shadows on the Teche’s early days as a sugar plantation through the Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow laws and desegregation, and the Civil Rights movement.

“Our ground rules are simple. The first one is that there’s no such thing as a good slave owner. The Weeks family made choices to move from England to Louisiana to create sugar and cotton plantations and to purchase and own people. We typically don’t allow visitors to get away with the idea; that was how it was back then. The second ground rule is that there’s no singular experience,” explains Adam Foreman, Senior Manager for Interpretation and Communication at Shadows on the Teche.

Commemorating Enslaved Individuals

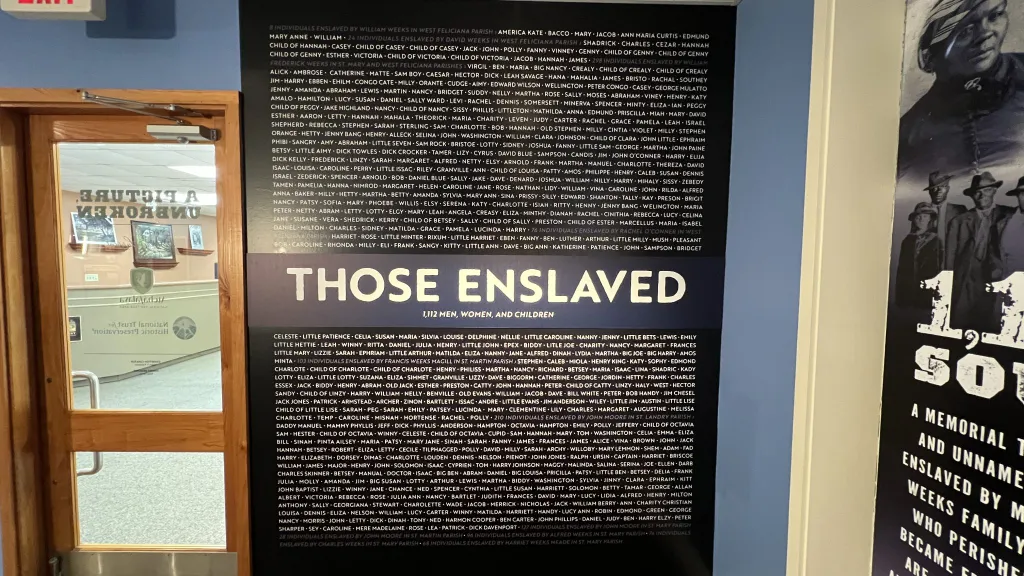

A wall that reads 1,112 Souls at the exhibit entrance lists the names of enslaved people who worked and lived at Shadows on the Teche. “The memorial has 700 names of those enslaved people, and we’re still working to find the remaining names,” Adam explains. The wall is an homage to those named and unnamed enslaved individuals, including those who perished in infancy or became freedom seekers and those lost to Antebellum historical records.

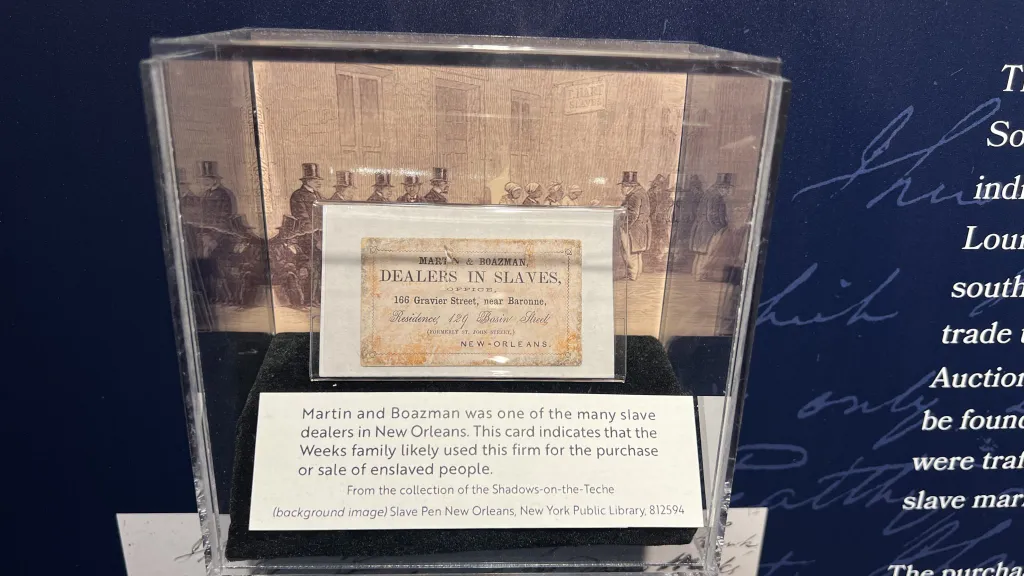

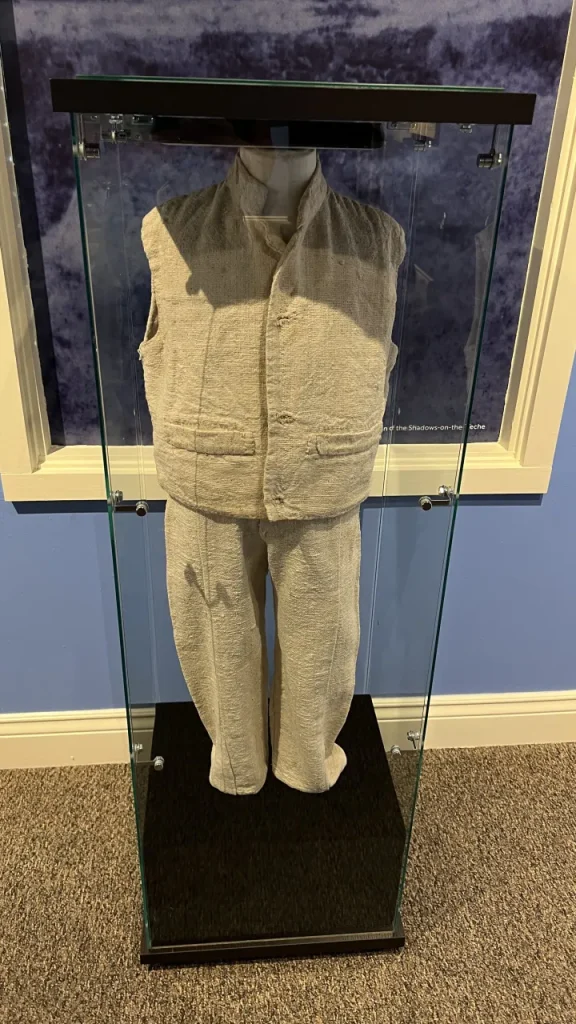

The exhibit displays ephemera from the Weeks’ archives, including the business card of a slave broker and an enslaved child’s outfit.

Artifacts excavated around slave cabins offer a glimpse into the daily lives outside of work, including a small doll and a clay marble. “The marble tells us that enslaved children played and created a life for themselves. They figured out how to survive their condition. For a long time, the narrative was limited to labor and how they worked in the fields, without considering their existence as a full person and their humanity,” Adam says.

The exhibit also pays tribute to the home’s last owner, William Weeks Hall, an artist and preservationist. His paintings are on display.

Touring Shadows on the Teche

A Picture, Unbroken provides historical context for the home tour and aims to stimulate deeper conversations.

Shadows on the Teche is one of the few existing antebellum homes that remained in the family until it became a museum. The home retains most of its original furnishings, decor, and objects, accurately recorded with receipts, letters, and other ephemera, totaling more than 17 thousand items in the Weeks family archive.

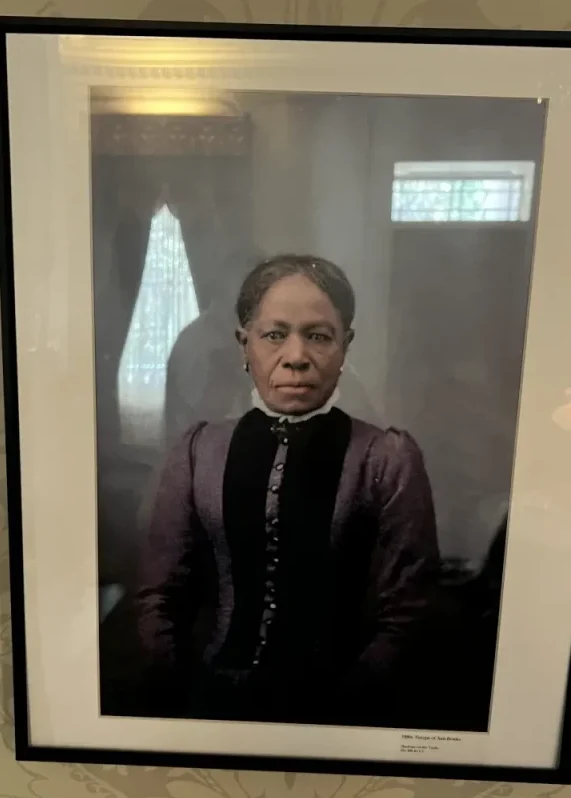

As you enter Shadows on the Teche, the first room chronicles life for the enslaved people who worked on the sugarcane plantation. Images of slave workers from the property’s collection populate the walls. The black and white images are colorized to humanize the photos of slaves. “The Weeks family owned around 2000 acres of land on Weeks Island, and they enslaved around 300 people on that island,” Adam explains.

The next room houses the kitchen, where eight slave outfits for children are displayed, sewn by an enslaved seamstress named Charity. “The outfits date to 1866 and are extremely rare, and we know that because we have a letter in which the Weeks family complained about the clothing. The Weeks were upset because Charity didn’t follow a standard pattern to create a one-size-fits-all outfit for the enslaved children. Instead, she customized each outfit. They just threw them into a trunk and made Charity start again, so this clothing was never worn,” Adam says.

The clothes raise more significant questions about the relationships between owners and the enslaved, absent archival documents outlining the perspective of the enslaved. “We don’t know whether Charity disobeyed orders to sew the clothing according to a pattern as an act of defiance or as an act of humanity.”

Historical and Social Context

We move into the dining room, adorned with fixtures, furnishings and objects typical of wealthy southern planters. Portraits of the home’s owners, Mary Weeks, the original owner, and her second husband, John Moore, hang on the walls overlooking the dining table. Mary’s first husband, David, died before Shadows on the Teche was completed.

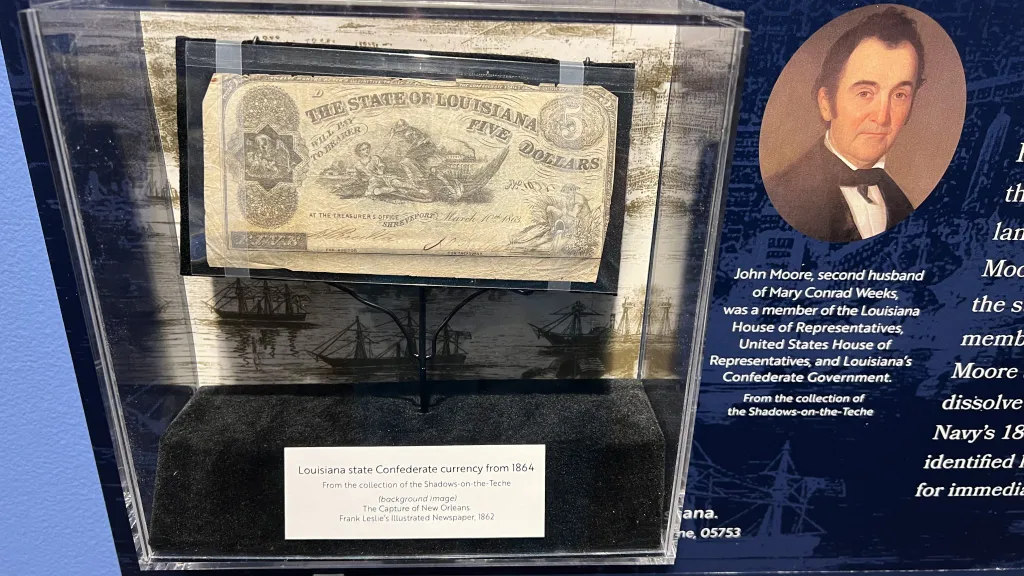

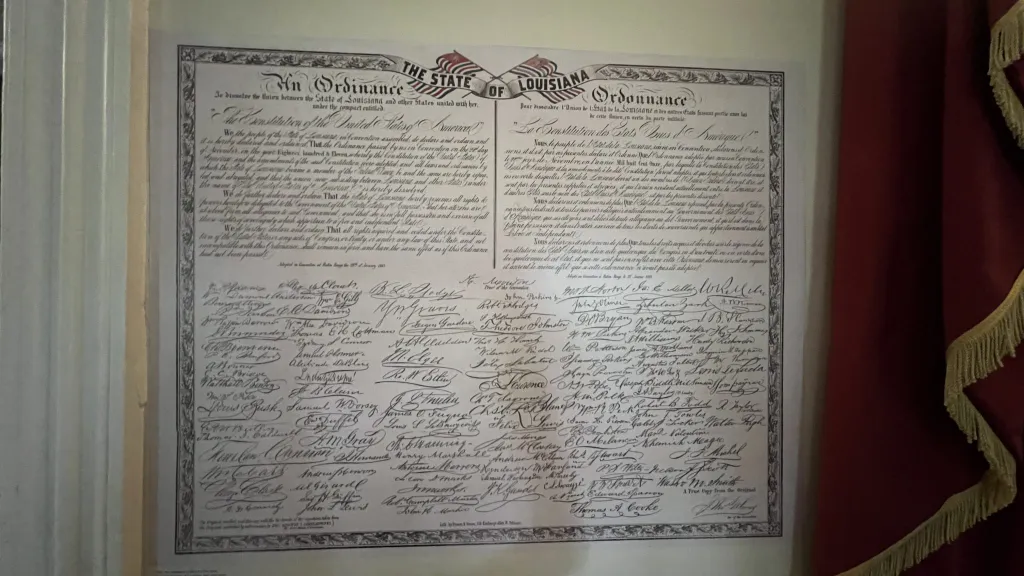

John Moore owned two plantations, one near Franklin and another near Opelousas. “John was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and a member of the Confederate government. He helped write the Articles of Secession that split Louisiana away from the Union,” Adam says.

A copy of the ordinance of secession with his signature hangs on the wall. In the dining room, Adam talks about how Mary managed the plantation after her first husband died, turning it into a profitable business. “We ask a complex question about what they think relationships look like between the enslaved people on the property and Mary and the Weeks family. It challenges our visitors to think more deeply about systems of slavery and how these two very different societies dealt with each other.”

There is a glamorous story about The Shadows on the Teche, a place frequented by famous names of its time. Many of those names are autographed on the bedroom door on display in the art studio belonging to William Weeks, the home’s last owner.

Personal Stories and Legacy

William was a “Bon Vivant” in the 1920s, an artist who moved in famous name social circles as an openly gay man.”William lived a dual life, one as a public figure in New Iberia, and a second life as a queer man in Louisiana during the 1920’s, which was a relatively dangerous time for queer people.”

In Mary’s room, a colorized portrait of Charity, the enslaved seamstress, hangs over the fireplace mantle. “This photograph was taken in the 1880s, after the American Civil War. Charity did not continue working for the Weeks family after the war. We know that she settled on Weeks Bayou, near Weeks Island where she lived with her son and her grandchildren until she passed.”

During the Civil War, Mary remained in the home, confined to her upstairs bedroom while Union Troops commandered the home as a headquarters. Mary died in her bed in 1863, and her son William Frederick inherited the plantation.

“William Frederick restarts the plantation after the Civil War ends using advantageous labor contracts that bind freedmen back to the land because of the debt they owed. Workers receive payment once a year, placing all of their expenses on credit. When they were paid at the end of harvest, their paychecks didn’t cover the debt, so they had to sign another labor contract and continue working on the plantation to pay off their debts. This type of exploitative labor contract is one of the first steps toward the Jim Crow system in Louisiana,” Adam says .

“In Mary’s bedroom, we talk about the decline of The Shadows. Lily Weeks, William Frederick’s daughter, inherits the home and plantation with her sister. In 1898, they invested in a salt mine on Weeks Island. In 1919, a huge fire destroyed the salt mine, ending sugar production on the island and the family business.”

Historical Reflections and Future Plans

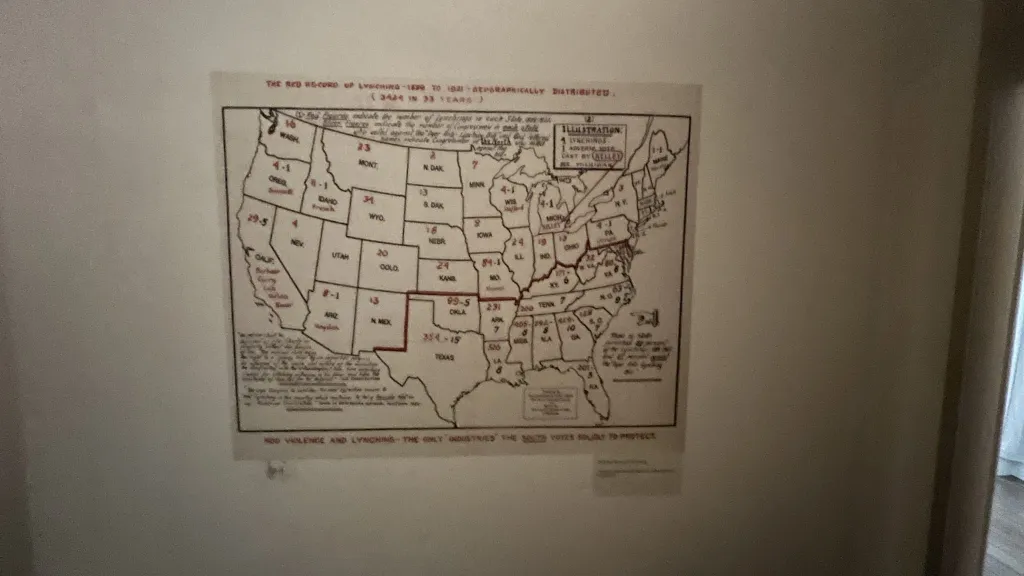

Behind the bedroom door, a map of lynchings around the nation serves as a grim reminder of Louisiana after the Civil War, during the Jim Crow years. After Union Troops left the South in 1877, freed slaves struggled to maintain their fundamental rights as oppressive Jim Crow laws that disenfranchised black people took hold of the South.

“This map tracks the number of lynchings in a state over 33 years in Louisiana, which amounted to 326 lynchings. The map came from the National Archives and was published in 1921 because the US Congress tried to pass an anti-lynching law but failed. Congress tried to pass anti-lynching laws over 200 times until 2023, with the passage of the Emmett Till Bill.”

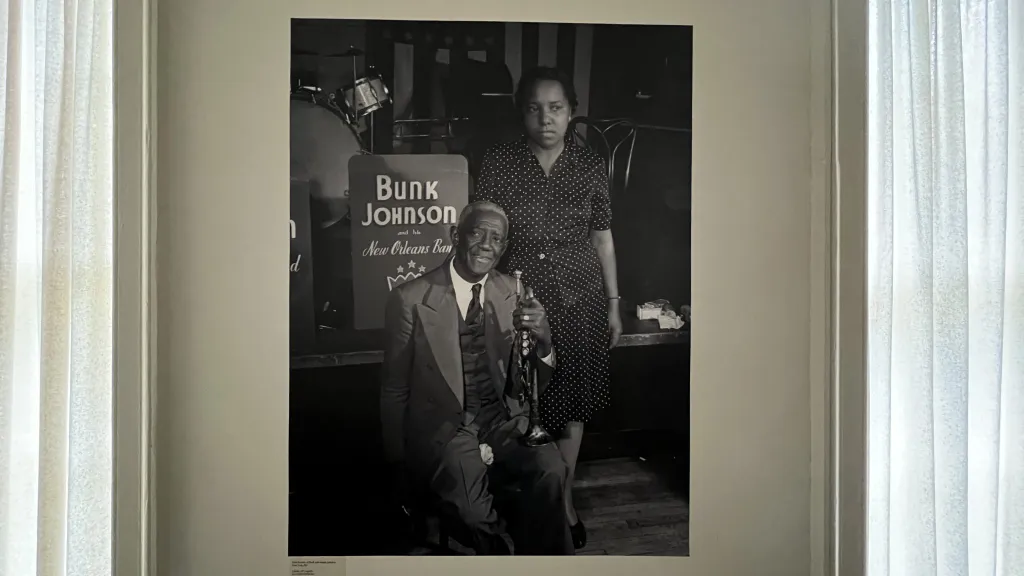

The final room on the tour is an homage to the Harlem Renaissance and local black musicians, including Bunk Johnson, a jazz legend, and Wilfred Russell, whose trumpet is on display.

Future plans call for digitizing the Weeks family archive of 17 thousand documents, making it available online. Currently, the collection is housed at LSU. The written firsthand accounts of life at Shadows on the Teche are absent from the archives because most enslaved individuals didn’t know how to read and write. The Louisiana Endowment of Humanities is funding an ongoing series of community outreach programs focused on the inclusive narrative of Louisiana’s Antebellum history.

Click to watch for a tour of the museum and home:

Discover More About Louisiana

8 Cultural Experiences & Museums in Louisiana You Can’t Miss

Journeying the Great River Road: South Louisiana Highlights

Louisiana Mardi Gras: A Behind-the-Scenes Look and Fascinating History

The Legacy of Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame & History Museum

The National Hansen’s Disease Museum

Here’s Why Hunt Slonem Paints the Same Bunnies Over and Over