This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission from purchased products at no additional cost to you. See my full disclosure here.

On July 4, 2026, the United States will mark a milestone: the Semiquincentennial. What better moment to retrace the footsteps of the patriots, to feel the tension in the streets and harbor, and to walk the ground where America’s bold experiment was born. In honor of America’s Semiquincentennial birthday, The Design Tourist is presenting a series of travel articles exploring the nation’s founding cities. The 13 original colonies were the first British colonies in North America that eventually formed the United States. They were located along the Atlantic coast, stretching from Massachusetts in the north to Georgia in the south. I invite you to explore and perhaps plan a trip to the places that played a significant role in the nation’s creation.

I begin my America’s 250th Places to Visit travel guide in Boston, Massachusetts, where you can traverse the Freedom Trail, walking in the footsteps of revolutionaries. The Freedom Trail runs 2.5 miles along a red-brick path connecting 16 historic sites that played a pivotal role in the American Revolution and the birth of American independence.

A City in Revolt: Boston as Epicenter

Boston was more than a colonial outpost — it was a crucible of dissent. Its merchants, printers, clergy, and everyday people felt keenly the burden of British policy: taxation without representation, enforced trade restrictions, punitive acts passed by a Parliament oceans away. As anger mounted, Boston became the stage for confrontation, protest, and ultimately, revolution.

When you walk Boston’s Freedom Trail today, you walk through a living narrative. The red‑brick line winds 2.5 miles, connecting 16 sites where ideas were argued, speeches made, bullets flown, and liberty declared.

Walking the Freedom Trail: A Revolutionary Pilgrimage

Below is a suggested path and commentary to bring alive your stroll through Boston’s revolutionary past.

Boston Common

Start at Boston Common, the nation’s oldest public park (est. 1634). It’s fitting that your pilgrimage begins amid open green space, historically used for cattle grazing, public gatherings, and eventually as an Army encampment. A 10–12 minute walk from Boston Common leads to the Old State House, built in 1713 and immortalized as the scene of The Boston Massacre.

The Old State House served as the seat of the Massachusetts colonial and later state governments, residing in the heart of Boston’s financial district. Here, on March 5, 1770, British soldiers fired into a crowd, killing five colonists, an event that led to the American Revolution. From its balcony, the Declaration of Independence was first read to Bostonians on July 18, 1776. Today, it’s a museum operated by the Bostonian Society, standing as one of the oldest surviving public buildings in the United States.

A short climb brings you to the Massachusetts State House, with its gilded dome (originally wood, later covered by Paul Revere’s copper works, and eventually gilded in gold leaf). The building is still the seat of state government and offers free weekday tours.

Granary Burying Ground & King’s Chapel

Nearby lies the Granary Burying Ground, final resting place of icons like Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Paul Revere, as well as victims of the Boston Massacre. A quiet place to reflect.

Just across the street is King’s Chapel and its adjacent burying ground, a reminder of Boston’s religious, social, and political layers over centuries.

Old South Meeting House

Next, walk to the Old South Meeting House, where colonists gathered to protest British taxation and where, in December 1773, crowds gathered before the Boston Tea Party.

Freedom Trail Stops along Boston’s North End:

In 1630, the first settlers arrived to Boston’s North End, and by the late 1800s, the area attracted Italian immigrants who settled and created the neighborhood known as “Little Italy.” The Freedom Trail enters the North End by crossing the Charlestown Bridge toward the USS Constitution and Bunker Hill Monument

Faneuil Hall & Quincy Market

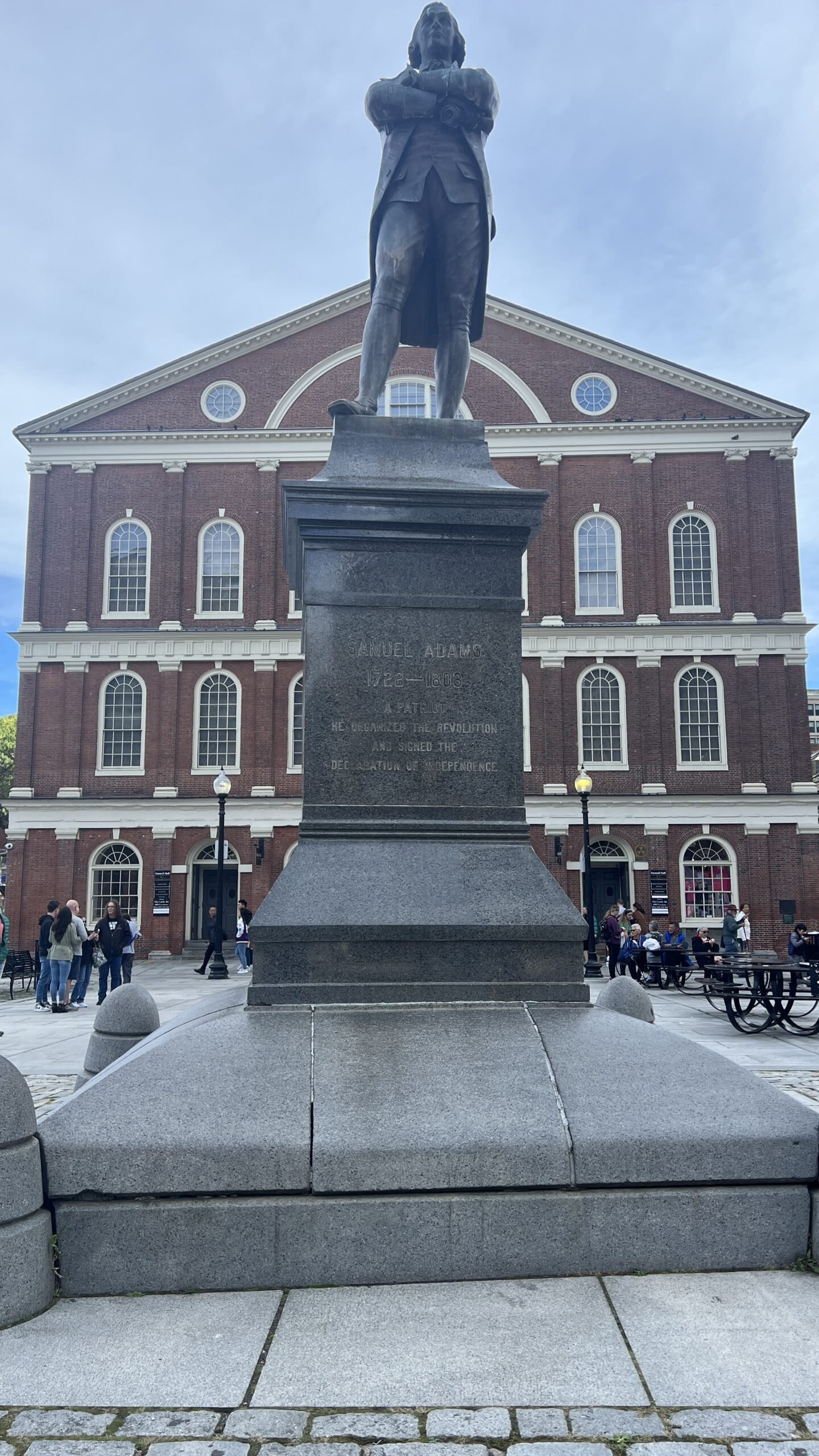

Faneuil Hall is one of Boston’s most iconic landmarks, serving as a meeting place during the American Revolution. Peter Faneuil, a wealthy merchant, built Faneuil Hall in 1742 as a public market and meeting hall. American Revolutionary leaders, including Samuel Adams, James Otis, and others, gave speeches protesting the Sugar Act (1764), Stamp Act (1765), and other British taxes.

Today, Faneuil Hall is a popular marketplace and is part of the Boston National Historical Park. Here you can explore the historic assembly hall and shop at Quincy Market built in 1826 and filled with food vendors selling local favorites including Boston clam chowder and lobster rolls.

The North and South Market Buildings flank Quincy Market, populated with boutique shops. A bronze statue of Samuel Adams stands outside the hall and on the rooftop of the hall sits the Grasshopper Weathervane, a golden grasshopper crafted in 1742, used as a “test question” to catch spies during the Revolution

Paul Revere House

Located at 19 North Square, the Paul Revere House is the oldest surviving structure in downtown Boston, dating back to 1680. It resides next to the North Square, one of Boston’s oldest public squares. Patriot Paul Revere, who worked as a silversmith, set out on his famous “Midnight Ride” in April 1775. Visitors can tour period rooms and see artifacts from Revere’s life.

Then cross a few narrow streets to the Old North Church, where on the night of April 18, 1775, two lanterns hung in the steeple signaled “one if by land, two if by sea” — alerting militia that British troops were coming by water.

The Old North Church is officially called Christ Church in the City of Boston, is famous for its role in Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride. On April 18th, 1775, Paul Revere instructed the church caretaker to hang lanterns warning that the British army would soon be heading over by sea to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Paul Revere’s midnight ride is one of the seminal events of the American Revolution. Two lanterns were hung that night, signaling that the British were crossing by sea (via the Charles). This became immortalized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem Paul Revere’s Ride. The signal allowed messengers like Revere, William Dawes, and Samuel Prescott to warn militias in Lexington an Concord.

Built in 1723, the Old North Church is the oldest standing church in Boston, and its steeple, at the time, was the tallest structure in the city. Today, it is a National Historic Landmark visited by millions on Boston’s Freedom Trail and an active Episcopal congregation.

Nearby is Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, Boston’s second-oldest cemetery. During the Revolution, British troops used the gravestones for target practice; here lie craftsmen and artisans like Robert Newman, the lantern‑hanger.

Freedom Trail Stops along Boston’s Seaport:

The Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum:

The Boston Tea Party took place on December 16, 1773, and accelerated tensions between the American colonies and Britain. On that day, a group of colonists known as the Sons of Liberty, disguised as Mohawk Indians, boarded ships in Boston Harbor and dumped 342 chests of tea into the water. The act was in protest to taxation without representation, especially after the Stamp Act (1765) and Townshend Acts (1767). The event radicalized colonial resistance. Within two years, tensions culminated in the Battles of Lexington and Concord (April 1775), the official beginning of the American Revolution.

The Boston Tea Party Museum recounts these events through actors in character and reenactments. You can board the ship and throw tea crates overboard.

Charlestown: USS Constitution & Bunker Hill

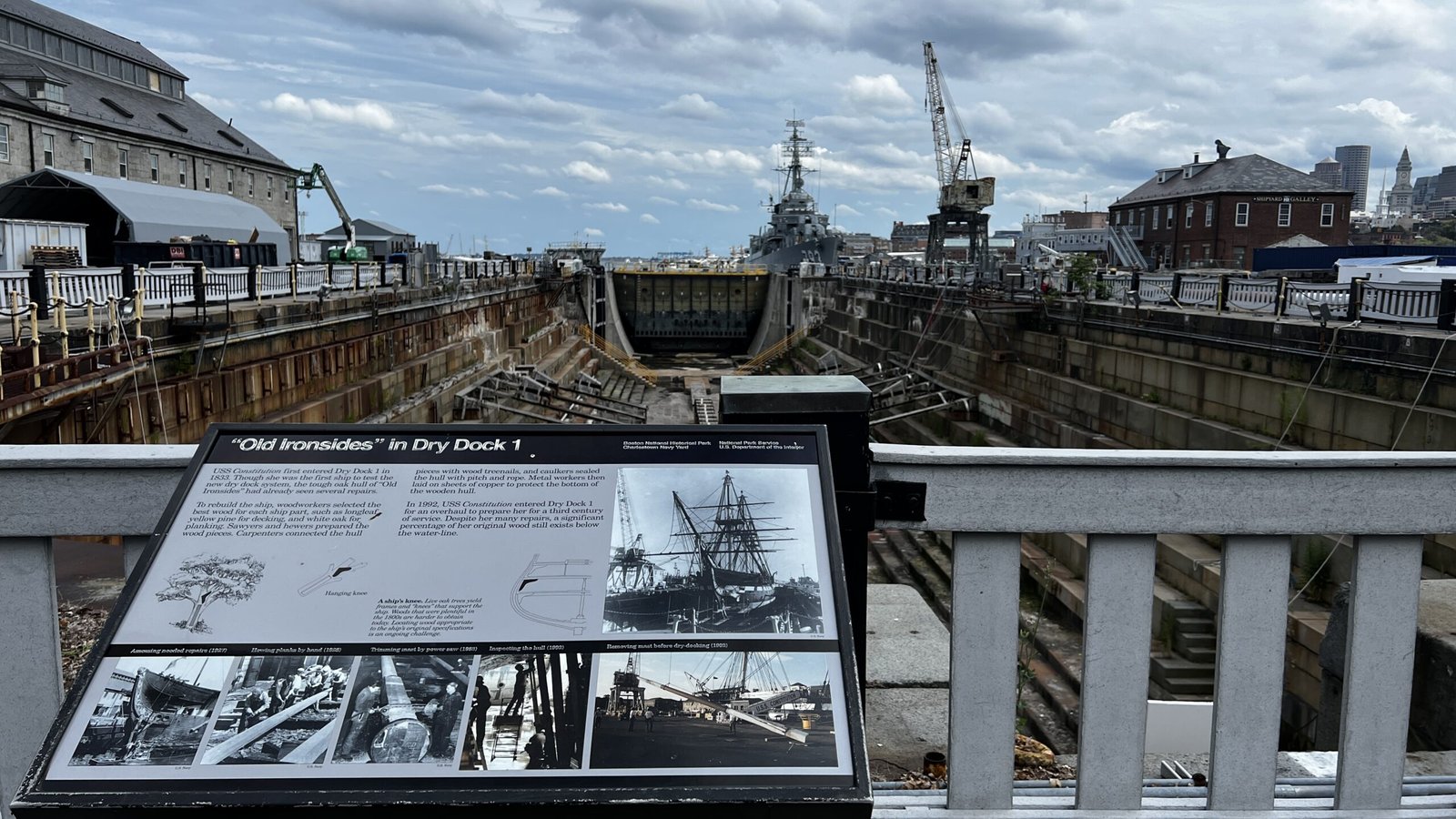

Cross the Charlestown Bridge toward the Charlestown Navy Yard, home to USS Constitution (“Old Ironsides”) and its museum — a symbol of early American naval resilience.

The Navy Yard resides in the Boston National Historical Park, offering tours of the oldest commissioned warship afloat, a museum, and a dry dock. The ship is known as Old Ironsides, launched in 1797, and earned her nickname by deflecting cannonballs during the War of 1812.

Dry Dock 1, where Old Ironsides went for repairs, is on view. The USS Constitution first entered Dry Dock 1 in 1833 for maintenance, and in 1992, the ship underwent an overhaul at the dock to prepare her for a third century of service. Today, a significant percentage of the original wood still remains below the waterline.

Visitors can explore the ship with Navy sailors as guides. Walk below deck to see the captain’s living quarters, the kitchen, and the sailors’ living spaces.

The USS Constitution Museum chronicles maritime history and stories of the War of 1812. The museum also acknowledges how the Navy used enslaved labor to harvest timber and build the dock and ship.

In 1853, the Constitution joined the international fight against slavery, intercepting ships illegally transporting people from Africa to Cuba.

The Freedom Trail culminates at the Bunker Hill Monument, a 221-foot obelisk commemorating the fierce 1775 battle. Climb its 294 steps for sweeping views of Boston and reflect on how early bloodshed fueled the fight for freedom.

Beyond the City: The Battlefields of Rebellion

No trip to revolutionary Massachusetts is complete without leaving urban streets for the quiet roads of Lexington and Concord.

Lexington Battle Green

About a 30‑minute drive from Boston lies Lexington, where, on April 19, 1775, colonial militia confronted British regulars on the town green. The first shots of the Revolutionary War were fired here. Stand where militias faced down redcoats in the pre‑dawn hours of rebellion.

Minute Man National Historical Park (Concord)

In Concord, the North Bridge marks the spot of the “shot heard ’round the world.” The Minute Man Visitor Center offers multimedia exhibits, ranger talks, and interpretive trails. Walk Battle Road Trail, the scenic path through fields and woods connecting skirmish sites between Concord and Lexington — a chance to feel how conflict ruptured the New England countryside.

Quincy & the Adams Legacy

Just south of Boston lies Quincy, the hometown of John Adams and John Quincy Adams. Tour the Adams National Historical Park, including their homes, gardens, and tombs. Walk the Presidents Trail, where you can reflect on how the fight for independence shaped the lives of those who led the early republic.

Travel Tips & Reflections for the 250th

- Pace yourself. The Freedom Trail is walkable in a day, but better enjoyed over two—one day for the city, another for Charlestown and Quincy.

- Guided vs self‑guided. Explore on your own using maps and audio guides, or let costumed interpreters bring characters of the Revolution to life.

- Timing matters. Spring through fall offers the fullest access; winter can be cold and museums may have limited hours.

- Stay nearby. Choose lodging in Beacon Hill, Back Bay, or the North End to keep you within walking distance of many sites.

- Connect to Philadelphia. After Boston, continue your 13‑colony odyssey by heading to Philadelphia — where the Declaration was signed and a new nation took shape.

Why This Matters, 250 Years Later

Walking Boston’s streets, visiting battlefields, and touring Adams’s home — you’re not just seeing history; you’re standing in it. You witness the swirl of courage, conflict, compromise, and conviction that birthed a nation. In 2026, as America celebrates 250 years, these places invite us to remember both the ideals and imperfections of our beginnings.

So lace up your shoes, breathe in the Atlantic breeze on Boston Harbor, let the red bricks underfoot guide you, and listen — for in these stones, in these churches, in these fields — the voices of liberty still echo.

Would you like me to draft a companion piece for Philadelphia next? Or help build a day‑by‑day itinerary for Boston + Philadelphia for 2026?

Experience Your Destination with Plannin

Travel is more than sightseeing—it’s about immersion. With Plannin, you can:

✅ Discover authentic adventures, culture, history & cuisine

✅ Unlock hotel deals worldwide at exclusive rates

✅ Book everything in one place—fast and hassle-free

Turn your next trip into a story worth sharing.

Plan your journey with Plannin today.

Stay Connected Anywhere with Saily eSIM

Traveling soon? Skip the hassle of buying local SIM cards and enjoy instant connectivity with Saily eSIM.

With Saily, you can:

- Activate mobile data in minutes—no physical SIM needed.

- Choose affordable plans in over 150 countries.

- Keep your WhatsApp, contacts, and number without switching.

Whether you’re exploring cities or remote getaways, Saily makes staying online easy and affordable.

Get your Saily eSIM now and travel worry-free.

Read More:

Natchitoches American Cemetery: Oldest Cemetery in Louisiana Purchase